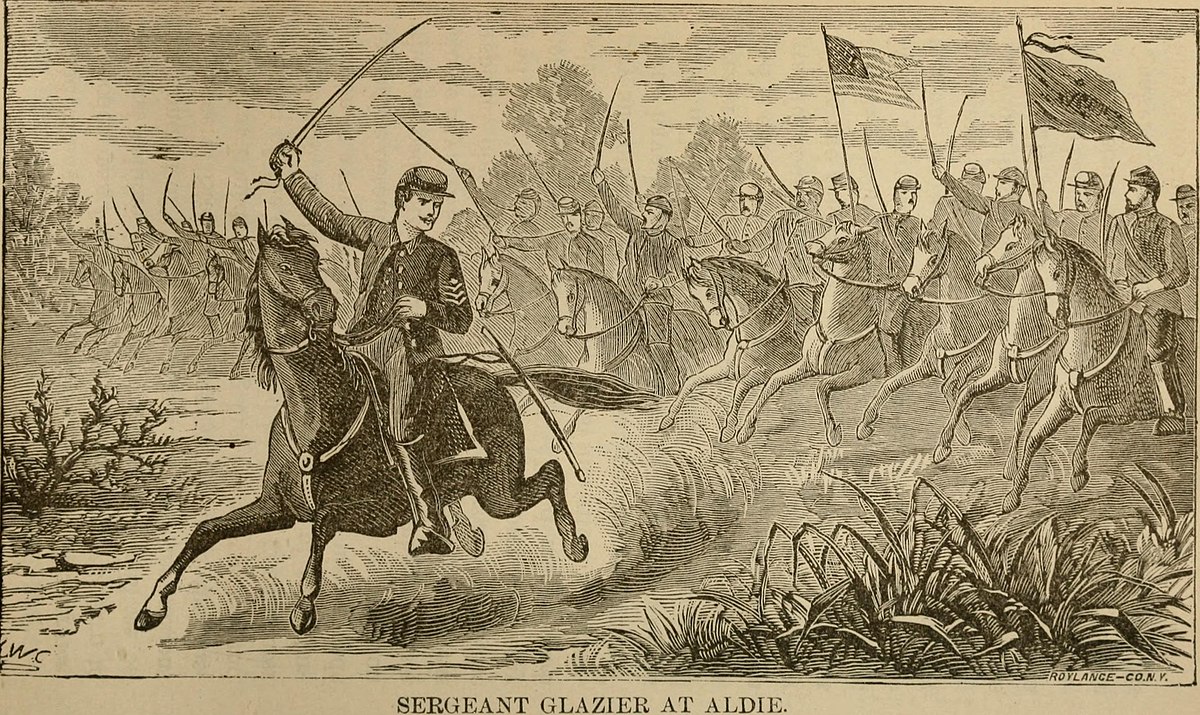

Willard Glazier was the ultimate ironman and a peerless survivor. He lived by his sword and by his pen.

The quintessential self-made man grew up poor on a farm in St. Lawrence County and dropped out of school to make a living as a trapper in the wilds of the North Country. He saved enough to buy a horse and at 18 rode to Albany. He enrolled in 1859 at the State Normal School (now the University at Albany), with the intent of becoming a teacher. He ran out of money after a semester and had to leave, but he picked up temporary teaching jobs in rural Rensselaer County while periodically returning to college when he had enough cash.

In 1861, Glazier, most of his college classmates and two instructors enlisted in the Union Army. Since he had a horse, he was assigned to cavalry and the 2nd Regiment of New York.

He was taken prisoner Oct. 18, 1863, in a Civil War battle at Buckland Mills, Va. He escaped from confinement in Columbia, S.C,. was recaptured near Springfield, Ga., escaped again and with the help of several African-Americans, made his way safely back home to Albany. But his term of service had expired and he re-entered the Union Army as 1st lieutenant with the 26th New York Cavalry. He served with valor until the end of the war and was promoted to brevet general for “meritorious service.”

He married Harriet Ayers of Cincinnati in 1868, an understanding wife who supported Glazier’s unquenchable wanderlust.

He transformed himself into an explorer and adventure travel writer. He rode a horse from Boston to San Francisco, beginning in 1875 and finishing a year later. He was captured by Native Americans in the Wyoming territory and escaped, which helped sell copies of his

book, “Ocean to Ocean on Horseback.”

In 1881, he set out to travel the entire 2,300-mile length of the Mississippi River by canoe. His adventures yielded two books and the discovery of what he considered the true source of the Mississippi. Although it was disputed as the source, Lake Glazier was named in his honor.

In addition, he organized a regiment for the Spanish-American War, had a river named for him after exploring uncharted territory on the Labrador peninsula, wrote several best-selling books and lectured around the U.S.

Glazier traveled a lot of hard miles and died at age 64 in 1905. His final resting place is among “Millionaires’ Row,” in Section 29, Lot 26, and his large granite marker is strikingly visual: crossed swords, a bugle, canteen, a waving American flag and a long list of accomplishments that kept a stone carver’s chisel ringing for days.

http://www.timesunion.com/albanyrural/glazier/

IT

IT  FR

FR  DE

DE  EN

EN