Life of a Victorian adventuress: Incredible story of clergyman's daughter who braved malaria, floods and wars to trek across China

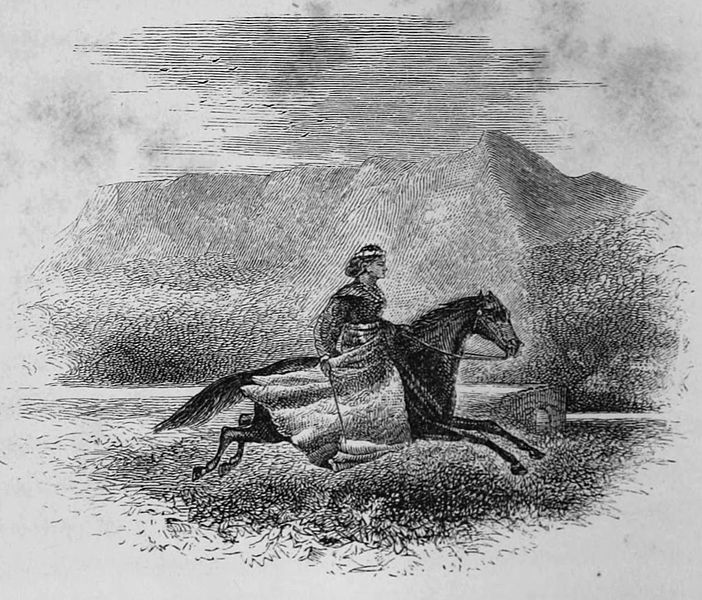

At a time when few women would leave their houses alone, Isabella Bird braved war, floods and male scorn to complete arduous solo journeys in America and the Far East.

From 1894 to 1897 the Victorian explorer trekked across China while it was with war with Japan, documenting the lives of the men and women she met through detailed written accounts and a collection of vivid photographs.

Some of her incredible journeys, published in her 1899 work in The Yangtze and Beyond, are now the subject of a new book by Deborah Ireland.

'She was the most incredible woman, and a true role model for women today,' Ireland told MailOnline Travel.

'Isabella didn't become famous as a travel writer until she was 44 - at that time women just didn't have careers as writers. And it wasn't until she was 60 that she discovered photography. She broke the mould.'

In her book, Ireland charts Bird's three years spent travelling in China and reprints her stunning photographs of Chinese daily life gradually being infiltrated by European clothing and customs.

Isabella Bird turned to writing as a way to make money for her and her unmarried sister

Born in 1831 the daughter of a clergyman, as Ireland writes: 'The adventuress who travelled and rode in all weathers, exploring remote and dangerous regions, was writing about a life in sharp contrast to the one originally envisaged for her.'

The intrepid Yorkshire woman started writing in 1854 when she travelled to America to mend a broken heart. But it wasn't until 1875 that she found fame with an account of her experiences in Hawaii.

Bird was on her way home from an ill-fated trip to Australia when she fell in love with the islands. She initially wrote extensive accounts of her escapades to her sister, and decided that writing would provide a much-needed income for the unmarried pair.

On her return, Bird embarked on her publishing career and her candid accounts of her travel became instant bes-sellers, and she hasn't been out of print since.

Ireland writes: 'As a respected international traveller her views were sought by prime ministers, ambassadors and the newspaper men of the day.

'Her books were engaging, accessible and entertaining and she opened up a world of travel to the armchair explorer.'

Despite saying she was too old for arduous journeys, Bird travelled 8,000 miles during an extended trip to China, travelling on horseback and in carts, by boat and in a sedan chair, using her newly acquired camera and photographic skills to document her journey.

She traversed the country, from Hangchow (Hangzhou) to Hong Kong and from one end of the River Yangtze to the other as well as venturing into Korea and Japan.

In 1894 she set off from Liverpool to the Far East unaware she was travelling into the First Sino-Japanese War between China and Japan over control of Korea.

She was deported from Korea on a Japanese steamer with no money and luggage and only the clothes on her back and was forced to take refuge in China.

There she experienced a flood on the Manchurian Plain and risked her life helping drowning villagers in terrific storms before succumbing to malaria. She then broke her arm when the cart she was travelling in overturned just miles from the house of the missionary who was to take her in.

Confined to the town of Mukden (Shenyang) by her injuries, she spent time getting to know the missionary doctors and photographing their patients, many of whom suffered from leprosy or the effects of opium addiction.

Her photographs of this time show pagodas and palaces as well as the mean back streets and the ravaged faces of disese sufferers.

While travelling in the Chinese interior she managed to avoid the plagues of rats and other vermin by suspending her clothes and boots on the tripod of her camera.

She adopted Chinese dress as the tight fitting, tailored clothes she was used to were considered offensive by the local population.

However she did not quite escape the curiosity or hostility of the locals who were not used to seeing a foreigner, let alone a foreign woman, travelling.

Ireland writes: 'Overnight halts were a problem because of the stir she created by her arrival. This could range from curiosity to extreme hostility – from holes drilled through the walls of her room followed by whispering and giggling, to a full-blown riot with shouts of "Foreign devil", "Child eater".'

She also received the scorn of her countrymen, with archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard writing to her publisher's son: 'I must say I think the woman must be devoid of all delicacy and modesty who could travel as she did, without a female attendant among a crowd of dirty Persian muleteers and others.'

However Bird's account of her travels was hailed by one reviewer at the time as 'one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of late nineteenth century China ever written.'

In response to Sir Austen criticism, Ireland writes: 'Not bad for an account of a journey "undertaken for recreation an interest solely" or "but to satisfy her curiosity and love of travel".'

And what about Bird's legacy? 'Never give up! And don't think you're ever too old to do anything,' Ireland tells us. 'If you want, it's possible to have a new career at 60. She certainly did.'

www.dailymail.co.uk

IT

IT  FR

FR  DE

DE  EN

EN